[ad_1]

Cari Houghton Everhart distinctly remembers when her first-grade teacher at Hoover Elementary in Iowa City brought finger paint to class.

Then, to the kids’ surprise, she ate it.

It turned out to be pudding.

“So I have kind of warm, fuzzy feelings about my teachers there,” said Everhart, a Hoover student from 1980-87.

Those memories will remain for former Hoover students like Everhart, but the building’s demolition began Friday, marking the official end of a 65-year chapter in Iowa City education.

Although the Iowa City school board first voted in summer 2013 to close Hoover Elementary at 2200 E. Court St., it’s taken almost a decade to start tearing it down.

The freed-up space will be converted into tennis courts and expanded parking for nearby Iowa City High School. Staff from the district’s online-only school, who have been working out of the Court Street Hoover, will transition to a new building on the ACT campus the district is purchasing.

A decade ago, the fate of Hoover Elementary raised big questions for the Iowa City community. Among them were how to balance the desire for walkable, small neighborhood schools with larger, more efficient ones; how to best handle long-term facilities planning in a large, public school district; and how to communicate with the community in the process of answering questions like those.

The school that saw its last group of students in 2019 is often referred to as “old Hoover.” The larger, newer Hoover Elementary that replaced it in 2017, located about 2½ miles east, is thus referred to as “new Hoover.”

Everhart moved to Kansas after college. When she came back to her childhood Iowa City neighborhood in 2016, she sent her three kids to Hoover — despite knowing it would eventually close. She says it was the best welcome to Iowa City the family could have had.

“On the first day of school I asked my daughter if anyone talked to her and she said, ‘Oh yeah, I have lots of friends,'” Everhart recalled.

Everhart is among the handful of former Hoover students and parents planning to snag a brick from the old building as a memento.

“I remember all my teachers; I remember what classrooms I was in. I remember the feeling I had there, which was just a warm, caring environment,” she said.

Hoover’s history with its namesake, proximity to City High stand out

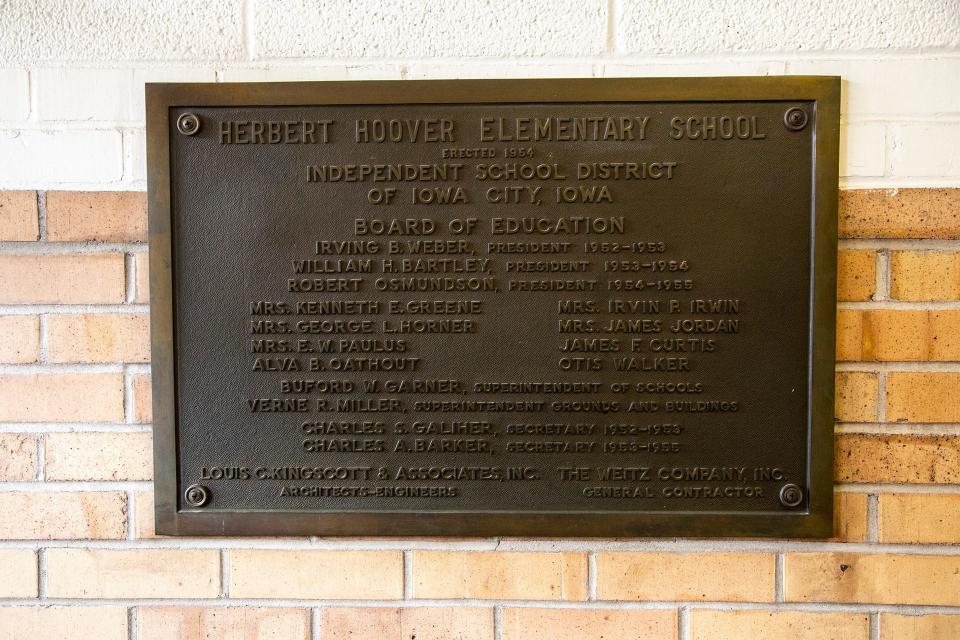

Iowa’s only president “dedicated” the school that was named in his honor when it opened in 1954. Herbert Hoover, born in the nearby town of West Branch, made the trip as part of his 80th birthday celebration.

The history stuck around.

Longtime Hoover teacher Lori Kriz remembers a “surreal moment” at the end of the year when graduating sixth-graders would touch the door handles the president used during the ceremony. Even when the handles had to be replaced, the old ones were mounted on a plaque so the tradition could continue.

Kriz began her career as a student teacher at Hoover in 1994. She never left, and now teaches third grade at the newer Hoover. Today, she remembers a key question in her interview for the job: What’s the difference between a colleague and a friend?

“I always thought that was such an interesting and an odd question in an interview. And I found out, in hindsight, those colleagues became my lifelong friends,” she said.

Many memories about the school revolve around its tight-knit community and strong sense of identity, all within an Iowa City neighborhood.

Everhart remembers seeing plastic sleds lined up in the hallways, ready to slide down the nearby snowy hill at recess. She and her daughter both had Dory Madden as librarian before she retired at age 88 after 55 years of working in the district.

Kriz remembers seeing third- and fourth-graders feel “excited and important” walking to the high school for track and field day. When she was teaching students about electrical wiring, her class walked to City High to check out the AP physics students’ model of the “Star Wars” Millennium Falcon.

“My third-graders looked at me and said, ‘That’s what we’re doing!’ And I was like, ‘That is so cool that they view themselves as the same degree of scientists and engineers as these AP physics kids. And you can’t have that experience if you can’t go directly to the source,” Kriz said.

But Hoover’s proximity to City High also ended up being a reason for its eventual closure.

In 2013, the school district began a long-term facilities plan that eventually added four new schools — the newer Hoover, Christine Grant Elementary, Alexander Elementary and Liberty High School — in response to projected enrollment increases.

The plan was to close the older Hoover, a smaller school, and free up space on the plot of land it shares with City High. Former Hoover kids would go to other neighborhood schools not far away.

Current school board member Maka Pilcher-Hayek was among the proponents of that facilities plan. Via email, she said she supported Hoover’s closure despite having three young kids who attended it.

“Closing a school is never an easy decision, but, when funding is limited by our state leadership, we make long-term decisions that are in the best interests of the entire school district community,” she wrote. “Public schools do not guarantee a specific building to a specific student; they guarantee an excellent education for everyone.”

The old Hoover housed students whose other schools were being renovated until 2019.

“It truly was a pretty amazing little community,” Kriz said. “And the new Hoover is an amazing community in its own right, in a different way. It’s a bigger school. Without the walkability of the neighborhood school, you make a community in a different way.”

Debate over Hoover’s closure reaches Iowa Supreme Court

Still, some held out hope the school would remain open.

In 2017, a petition began circulating that called for the school district to present the question of Hoover’s demolition to voters as part of a ballot measure. More than 2,300 people signed on to the idea — enough for the school board to validate it. But the board voted 4-2 against including it on the upcoming ballot, citing legal advice.

That year, three people filed a lawsuit in attempts to force the ballot measure — testing a legal question about school planning that had implications beyond Iowa City. It centered on the question of whether a school district is legally obligated to ask voters for approval before demolishing a school building.

Iowa Code says voters in a general election have the right to “direct the sale, lease or other dispersion of any schoolhouse or school site.” In the case of Hoover, Iowa City school district officials made the case that “disposition” has a different meaning from “demolition;” those advocating to preserve Hoover argued the opposite.

The case climbed to the Iowa Supreme Court. In 2019, its judges ruled the school district was under no legal obligation to obtain voter approval in order to demolish a school. The ruling said “disposition” must involve a transfer of an interest to a third party, which was not the case with Hoover.

In an interview last month, Del Holland, one of the three plaintiffs in the lawsuit, said he felt a sense of closure after the court proceedings came to an end.

“I accepted that in terms of, I haven’t done anything actively about the situation since then, because that was the ruling. That’s that. That doesn’t mean that I feel it was right, or correct,” Holland said.

Holland said the old Hoover allowed kids to go “dreaming up the sidewalk” on the way to school. A longtime teacher, he supports the idea of maintaining smaller schools and the benefits they bring for learning and walkability.

“We can afford to provide the best for our kids. And what we’re doing is building these monster schools and packing them in like crazy,” he said.

District in the midst of another facilities plan that may create new schools

Iowa City parent Robin Kopelman says between events like ice cream socials, committee meetings and school activities, elementary schools simply end up being places where people spend a lot of time.

Especially in her family’s case — all four kids attended Hoover — it’s only natural for the community to build a connection with their school.

“We’re sad to see it go; we’re fortunate that our kids are hopefully going to benefit in some way for what it will do for City High,” Kopelman said.

A new wing of City High opened this fall. More work is planned for the building as part of the current long-term facilities plan, the successor to the one approved in 2013.

Last school year’s district enrollment is similar to that of 2017-18, with a difference of only about 200 students. That’s below the projected growth discussed as part of the plan that led to Hoover being replaced.

The current plan also includes the potential creation of new schools. Also on the table is bulldozing and replacing Hills Elementary, the smallest school in the district that has been the subject of potential renovations for years.

More: Should sixth graders be in elementary school? Not anymore, according to Iowa City district

“I think once it’s torn down, and it’s completed for City, it’s going to be a good memory,” former school board member Paul Roesler said of Hoover in an interview Friday. He supported the closure and had a who attended the school.

“It’s not the first school in the district that we ever closed. That happens. It’s the first one in a really long time, but it happened. And I think when it’s finally torn down and gone, I think that people will kind of move on.”

Cleo Krejci covers education for the Iowa City Press-Citizen. You can reach her at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on Iowa City Press-Citizen: Demolition of Iowa City’s Hoover Elementary on Court Street begins

[ad_2]

Source link

More Stories

Why More Parents Are Choosing Online School

Online School Tools That Boost Productivity

Breaking Myths About Online School Experiences